Day Trip to Croix: Home to Villa Cavrois, the Modern Chateau

About two-thirds of the way from Lille city centre to Roubaix lies Croix, a town on the Roubaix Canal and Marque River. It remained a small village until the 1870s when the textile industry introduced wealthy entrepreneurs and industrialists who lived in the neighbourhood. With wooded and quiet avenues, the suburb is home to middle-class residences, their crowning jewel of which is Villa Cavrois.

There may not be much else to check out around Croix, but the suburb is easily accessible from Lille via its public transport network run by Ilévia and makes for a lovely midway stop if you’re heading north to Roubaix. One-way tickets and day passes are available, with free transport covered by the Lille City Pass.

And in case you’re wondering, no, Croix is not related to the famed flaky croissant.

Contents

Getting to Croix

By Metro

Line 2 (the red line) runs from Lomme Saint-Philibert in the west to Tourcoing-Centre in the north and will take you from Lille-Flandres to Croix-Centre in 15 minutes.

By Tram

Line R (the green line) runs from Lille-Flandres to Roubaix Eurotéleport. If you’re visiting Villa Cavrois, there’s a tram stop in its namesake, only 20 minutes from Lille. Alternatively, Bol D’Air will take you to the southern tip of Barbieux Park, and Parc Barbieux will take you further north near the park’s centre.

What to See and Do

Villa Cavrois

Villa Cavrois was a firm favourite from my time in France.

As you approach by foot from the tram station, you’ll pass by quaint plots of land with manicured lawns, and the villa’s glory is hidden from view behind a sprawling garden. It’s a jaw-dropping moment when the modern, yellow silhouette emerges past the front door, and it looks like a picture-perfect property that came straight from the spread of a retro interior design magazine. Its neighbours in the suburb appear humble, even drab by comparison.

In the 1920s, Paul Cavrois, owner of modern textile factories in Roubaix, wanted a family home nearby. He entrusted the construction to the French architect and film set designer Robert Mallet-Stevens, whose futuristic works he admired at Paris’ International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, and gave him carte blanche over the design. A rival of Le Corbusier and an ardent supporter of the modernist vision, Mallet-Stevens planned everything and conceived the villa as a total artwork reflecting his choice of technical and aesthetic preferences down to the smallest detail.

Unfortunately, the war soon forced the Cavrois to escape to Normandy, with the villa taken over by German troops. When the Cavrois returned home after the war, they divided the villa into separate apartments until Lucie Cavrois died in 1985. Furnishings were auctioned, and a company purchased the home for demolition, plunging the villa into a dark period marked by vandalism and theft until the state took back ownership in 2001 and classified the villa as a historical monument. Still, it took 13 years – and 23 million euros – to restore the grounds to a state faithful to the original creation, a process made especially difficult as Mallet-Stevens had all his writings burned at his death. Luckily, his photo book had survived, providing a reference for restoration with the team searching for original furnishings sold worldwide.

The villa’s 60-metre-long facade is fashioned from reinforced concrete and clad in yellow bricks, almost like the yellow brick road from the Wizard of Oz rose into the sky. Although bricks were widely used in the region, Mallet-Stevens used 26 different moulds to craft the bricks to exact dimensions, ensuring that no brick had to be cut. Like a liner anchored in the middle of a garden, the villa earned the name “yellow peril” from its neighbours, who were unaware it would become a tremendous modernist architecture from the 20th century.

Yet despite its exceptionally modern exterior with clean lines and large glass surfaces, the estate plan references traditional French chateaus: a large hall in the centre servicing two symmetrical wings, one for the parents and one for the children and servants.

Mallet-Stevens conceived of rooms with their emotional and psychological nuances in mind, and the villa’s interiors bear similarities to his designs for Marcel L'Herbier's films. According to the architect, the living environment should reflect the psychology of its inhabitants – in this case, a bourgeois family. Each room curated different materials and colours to create a meticulous ambience inspired by the Art Deco, De Stijl, Vienna Secession, and Bauhaus movements. The wonder of it all is that he managed to weave a coherence throughout by using details such as his iconic clock (a reproduction can be yours for €780) and silver radiator covers.

With a pragmatic approach, he avoided excess ornamentation, expressing luxury through prized materials like marble and wood instead. Flanking these rich materials was the top-notch technology of its time. Most rooms featured integrated lighting planned with engineer and designer André Salomon, which directs light towards the ceiling in a way that mimics natural sunlight. The house was also equipped with electricity, a rarity for the 1930s, with a modern boiler room, a wine cellar, heat, filtered water, and a telephone in every room.

The central space in the villa is the immense double-height parlour where the Cavrois hosted guests. Soft light pours through the large, sweeping windows offering a striking view of the gardens, with a mezzanine overlooking the room and a sliding door opening to the dining room clad in green Swedish marble and black lacquered pear wood.

The decor here is predominantly green, with walnut armchairs and tables (repurchased from a Sotheby’s auction) warmed by the touch of Parquet Noël floors and yellow Sienna marble in the spectacular fireplace. There is a deliberate juxtaposition of angles against circular motifs, and the rooms emanate conviviality in a retro, quiet luxury.

Behind the dining rooms is the kitchen with large windows opening onto the garden, a highly unusual feature as utility rooms and staff were often relegated to basements without windows.

Here, Mallet-Stevens’ predilection for hygiene is on full display, presenting a stark difference from the other rooms. While also monochrome, it was deliberately designed to be entirely white (except for the checkered stoneware floor) and sterile like a hospital. Everything was designed to be practical and easy to clean with ceramic tiles and enamelled steel furniture that was perfectly integrated into the walls.

The kitchen table deserves a special mention: it is an original piece designed by Mallet-Stevens and found in the basement, the only piece of furniture that hadn’t left the house. Paired with it are new editions of the architect’s lacquered steel chair, an example of functionalist furniture that was tubular, stackable, and easy to carry.

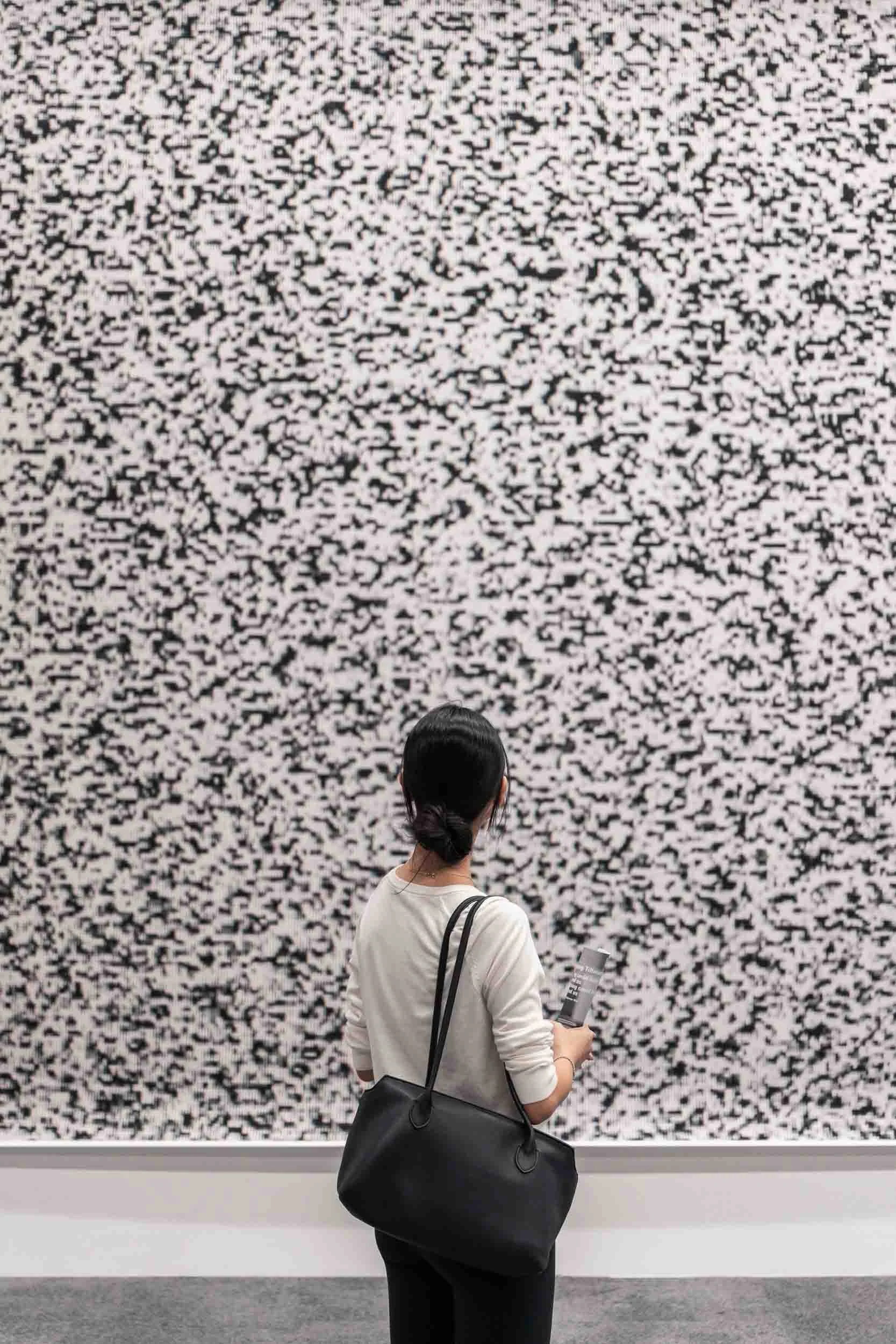

When we visited, there was a small architectural exhibition introducing equally striking villas, including the Villa Arbat (Moscow, Russia) by Konstantin Melnikov and Casa Malaparte (Capri, Italy) by Adalberto Libera.

Paul Cavrois’s study was furnished with varnished pear wood panelling and offered access to the smoking room, a circular space decorated in Cuban mahogany with leather bench seats reminiscent of a ship’s cabin.

The central tower is the only vertical element in the villa, creating a break in the horizontality of the complex. It houses the grand black and white marble staircase, a vertical bay window spanning multiple floors, and a belvedere on the top floor, a round space with a circular window offering a panoramic view of the gardens and Beaumont Hill. From afar, the cylindrical tower resembles an airport control tower, alluding to Mallet-Stevens’ past as an aviator during the war.

At the base of the stairs, a plague commemorates the dedication of Mallet-Stevens to the Cavrois:

“To Mr and Mrs Cavrois, who have allowed me, through their foresight, their defiance of routine and their enthusiasm, to create this house. With my gratitude and my loyal friendship.”

Upstairs, the east wing is dedicated to the master bedroom and bathroom, and the west wing to the children and housekeeper.

The master bedroom features creamy tones set against dark wood furniture, a two-toned theme recurrent throughout the villa. With indirect lighting and a large mirror to reflect natural light, the room is characterised by refined luxury and invites relaxation.

The parent’s bathroom spanned 50 square metres, with a carpeted dressing room for beauty treatments and another section with a bathtub and shower built in white Carrara marble. It was considered modern, with a water jet shower, a wall barometer showing the current temperature, and a scale set nestled into the marble trimming.

Lucie Cavrois’s boudoir is bright, with pale blue walls, lush carpet and upholstery, and sycamore furniture in almost yellow hues – a beautiful example of how modernist decor can be applied to feminine rooms. These furnishings were repurchased from private collectors, and the room has since been restored since it suffered fire damage when squatters occupied the villa.

The terrace pergola covered the rooftop of the west wing (the children’s wing), with 32 concrete beams serving as sunshades. It could be transformed into a dining room in good weather, with meals served directly from the electronic service lifts.

The outdoor pool facing the gardens evokes a chateau’s moat. Clad in yellow brick with crisp corners and two diving boards, the pool was yet another display of the villa’s modern spirit. Swimming was a prevalent sport between the war eras, and the villa’s 27-metre-long swimming pool reflects a burgeoning focus on hygiene and health.

Like classic châteaus, the gardens feature a 72-metre-long water mirror that reflects the villa and acts as an extension of the main hall and circular driveway. Rising above the gardens, the villa dominates the space almost theatrically, amplifying the visual continuity and perspective.

When Germans used the villa as a military barracks during WWII, the water mirror was filled in as it was deemed too visible from the sky and was only restored during the park’s refurbishment. Strolling to the garden’s end offers an unobstructed view that is just as magnificent as up close, with the edges of the water mirror drawing the eye back to the villa, a constant play on the inside-outside relationship of the project.

The garden initially extended over five hectares, but a subdivision in the 1990s caused the orchard, vegetable garden and henhouse to disappear.

Perusing the rooms and gardens of Villa Cavrois felt like moving through a film set back in time. Much of the villa’s modernity lies in the simplicity of its volumes as much as its state-of-the-art technology and industrial materials. The result was a contemporary chateau, brilliantly orchestrated to combine classical design and modern aesthetics, one that carried an air of elegance without being ostentatious. In some ways, it feels more practical and livable than modern housing — proof that less is often more, and you don’t need gaudy furnishings for a wow factor.

Mallet-Stevens Park

The Mallet-Stevens Park is located on the backside of Villa Cavrois and is dedicated to the architect in its namesake. The park covers an area of 2.5 hectares, with themed gardens and playground areas for younger children. Apart from the tunnels, there’s not much to look at, but the sprawling lawns make for an ideal location to picnic and relax in the heart of the Beaumont district.

Barbieux Park (Parc Barbieux)

Technically part of Roubaix, Barbieux Park is a long green strip almost halving the Croix commune, providing a haven of peace and nature for its wealthier residents.

It was initially intended to be an underground canal project in the 19th century that eventually fell through, leaving an abandoned hole in the ground. Under the landscape architect Barillet-Descamps, the town of Roubaix decided to use the site to create an undulating park crisscrossed with streams, ponds and waterfalls. With an area of 35 hectares and various rare plant species, the park was recognised in 1994 as one of the finest in France.

Church of Saint-Martin of Croix

Constructed in 1848 by the architect Théodore Lepers, the church was built in the Neo-Gothic style and clad in red bricks. While the exterior may look ordinary, the interior has been completely renovated and painted from floor to ceiling. Cobalt blue, burgundy and beige make up the colour palette, with intricately decorated pillars and a stunning vaulted ceiling over the nave. The church also sports several stained glass windows and a bronze statue of Saint-Martin by René Van der Meersch.

What to Eat

Barbara by Papà Raffaele

Barbara is the latest brainchild of the Papà Famiglia. A little further away from their home base in Lille city centre, the restaurant sports 70s disco-erotica vibes with cosy velvet seats and serves timeless Neapolitan pizza baked in authentic Napoli ovens, but also pizza al taglio – pizza baked on crispy focaccia bread, ready to be cut from rectangles just like in Rome. And, of course, a wide selection of their regular antipasti, desserts, and drinks.

Brasserie Cambier

Known as the “beer capital of France”, Lille is positively sparkling in its craft beer selection.

Brasserie Cambier is an urban craft beer brewery committed to bringing beer manufacturing to consumers. Their logo is inspired by the brewer's star, a symbolic representation of the four elements (water, fire, earth, air) involved in the brewing process.

The brewery produces two brands of beer: Mongy, a tribute to Alfred Mongy, the emblematic figure of the Second Industrial Revolution, and Cambier, a range of limited edition beers with a new beer produced monthly. To get up close, a hosted session will take you through the different stages of brewing, with tasting rounds included. Bookings are required online.

Where to Shop

La Maillerie

Also technically part of Villeneuve d’Ascq rather than Croix, La Maillerie is a short walk from the metro station Croix-Centre. The integrated lifestyle space is relatively new from 2021 and focuses on local merchants, promoting responsible and sustainable consumption in urban life.

Offerings include Les Halles de Maillerie by Biltoki (a gourmet market), Heavy Brick by Brique House (Texan barbecue crossover northern brewery with a brewing workshop), and a green rooftop with access to a vegetable garden operated by Growsters.

Where to Stay

Le Domaine des Diamants Blancs

Croix is entirely doable on a leisurely-paced day trip, but if you are on a road trip and prefer to stay and park outside of the Lille city centre, Croix is a reasonably close choice.

Le Domaine des Diamants Blancs is a care home complex (as evident in its name, The Domain of White Diamonds) that offers accommodation options with airy, modern interiors. There’s also an indoor swimming pool, albeit of smaller size. It’s a walk to the tram station, so drive to get around.

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning we receive a commission when you click and make a purchase.

Related Posts